A CEO friend once asked me whether he should hire a Chief Product Officer in addition to his Chief Technology Officer. The CPO would hire a bunch of product managers, while the CTO would continue to manage engineers.

My response was that there shouldn’t be a separation. Making it two orgs would introduce a lot of unnecessary frustration and inefficiency.

Fence-chucking tremendously slows down joint problem solving

For those who follow this blog, you know how important these 2 rules are to designing highly productive organisations:

- The 80% rule: each team should be equipped with the resources and authority to deliver 80% of their mission without outside dependency

- Eliminate friction: eliminate friction to close the loop quickly over and over again

When Product is separate from Engineering, “fence chucking” often happens. This is when Product does a piece of work and then throws it over the fence to Engineering to carry on with it. It’s off of Product’s daily plate.

The issue is that making new things is not like running a production line. There is a lot of back-and-forth throughout the process – because it’s a new thing! E.g. something turns out to be harder than anticipated, someone misunderstood something, there’s an edge case no one thought of, etc.

But when key people are in separate orgs, there’s a fence between them: different incentives, schedules, priorities, working practices, lack of knowledge share. E.g. a 5 minute unblocking discussion might not happen for several hours. Or what comes out of the build doesn’t actually solve the root issue. Or technical debt and maintenance issues go unaddressed. Or a product manager doesn’t understand the full implications of their design choice.

Sometimes in a company, fence chucking is unavoidable. But by separating Product and Engineering, you introduce fence chucking unnecessarily.

Hats first, job titles second

Forget about job titles and org structure for a moment. Just think about hats. A “hat” is a bunch of tasks that need to get repeatedly done.

Think about all the hats that need to be worn to build a market leading product. So for example, your company might have the following hats:

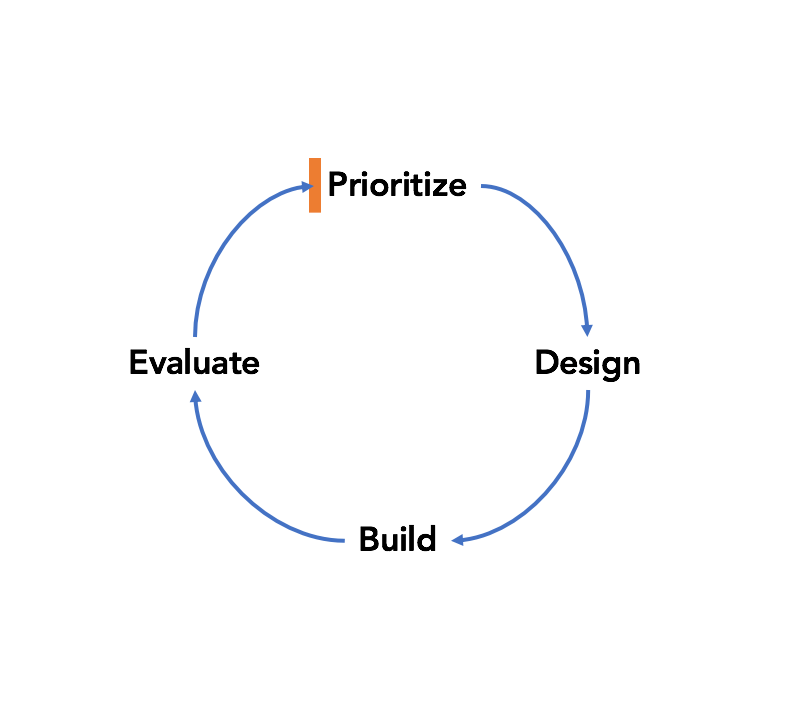

- Prioritisation: look at range of things we could be building + talk to sales and ops + do analysis = figure out what’s most important right now

- Sprint management: setup schedulers + keep tracking tool uncluttered

- Product design: really understand issue + brainstorm options + iterate on options + early wireframing + quick investigations = written design document

- Technical design: really understand issue + understand product design + design database models + design architecture = technical design points added to design doc

- Technical build: really understand issue + understand design + write code + write & run tests + review with colleagues = branch ready for release

- Etc.

There are a lot of hats. An effective team will wear most of those hats within itself (again, the 80% Rule!). However, 12 hats does not mean needing 12 people. 1 person usually wears multiple hats. And 1 hat could be shared by multiple people. It’ll vary depending on what makes your company special.

At the end of this, you might say that Sarah wears Hats A+B+E. And Jimmy wears hats B+C+D. Etc. You can then put a job title on that combination of hats.

But the title almost doesn’t matter. What does matter is that a) all needed hats are competently worn and b) these people are working directly with each other (rather than over a fence).

Don’t split “Product” and “Engineering”

For the question of Product vs Engineering, the hat exercise shows that they should be the same org, a unified team. For companies that have only an “Engineering” or “Tech” team delivering their product, that team is already a unified product development organisation. So when CEOs look at “adding” a product org, they’re actually looking at splitting out Product.

The question of making Product into a separate entity typically comes up because there is a “hat gap”. E.g. prioritisation sucks (e.g. random people ask developers to build something haphazardly). Or product design is weak (e.g. the solution is confusing, over-engineered, etc). Or tech leadership needs help to be more commercially minded.

If there is a gap, typically the best way to solve it is to:

a) ask existing people to wear the missing hats (if they have time, inclination and incentives)

b) hire someone to wear the missing hats (and incorporate them into the existing org)

c) change out the existing people (painful but sometimes the right answer)

Not spin up a separate department within the company!

The little unsexy things get done

A notable benefit of having unified teams is that it is simpler to get little unsexy things done. Examples are:

- Technical debt and maintenance: e.g. upgrading out-of-date software packages, doing a “proper” fix for that nasty bug solved last week, refactoring a chunk of code, etc.

- Efficiency improvements: implementing new tools and/or changing practices that help the team be more efficient

- DevOps improvements: e.g. building better reports and alerts for monitoring

- Small bugs and tweaks: minor improvements (e.g. tightening up the UI, tweaking copy on a page, etc) that generally take less than hour to do

When Product and Engineering are separate, the little unsexy things don’t get done typically because:

- Clash of incentives: Product is normally rewarded for delivering new functionality; not behind-the-scenes improvements. Therefore they will never prioritise these items

- Overhead of fence chucking: because it takes a non-trivial amount of effort to push an item over the fence, it’s not worth it for minor improvements

Cumulatively, not doing these items adds up to significant drag. Teams move slower, catastrophic errors get made, user trust declines, etc. So aside from eliminating fences, unifying teams result in better nuanced decisions.

Mindsets matter

To some people, unified teams is scary. Working with someone in a cross-functional team means knowing something about what they do (and vice-versa). E.g. a product manager should know something about database models, so that they can understand why the original product design won’t work with the current database.

It means stretching out of your area of expertise – and thinking more holistically. That stretch may differ from team-to-team or from year-to-year. It requires being honest about what you don’t know and enjoying learning new things.

Without teammates who are willing to embrace it, a unified approach won’t work.

It isn’t easy but it’s worth figuring out

I get why a CEO might bolt on a CPO and product org. For the CEO, it’s a straightforward way to fill a gap. And if the existing org isn’t able to adapt, it might be the only option. But it’s like buying 10 kilogram running shoes. Sure you can run the race. But you’ll never win it.

Organising around purpose (rather than function) and ensuring that the teams are reasonably complete is harder in the short-term. But in the face of serious long-term competition, it gives you a chance at winning.

GS Dun works on developing new ventures. The name is short for “get sh** done”, so while we can talk the talk, we prefer to keep our meetings short and just get on with it.