This is a post in a series about the 80% Rule for Designing Teams. As a recap, the rule is that “each team should be equipped with the resources and authority to deliver 80% of their mission without outside dependency”.

The last post explained some of the limitations of organizing by function. The main drawback is that in larger companies, a lot of time is needed to manage each other.

For this post, let’s look at what it means to implement the 80% Rule. We’ll again use our example of EdCo, the fictional online education company, and the Primary School Team.

The team should be mostly self-contained

Suppose the Team’s mission is “deliver the best online Primary School courses in the country”. It should contain developers, course designers, marketers, and almost anything else needed to deliver the mission.

There are two major advantages to organizing by mission, rather than function.

- Reduce time spent coordinating managers of functional teams (more here).

- Team members are experts about the customer. This expertise is the difference between getting the details exactly right and just approximately correct.

These two advantages yield a third advantage: agility. In rapidly responding to competitor action or new insight, a self-contained team with knowledge and resources can act without spending weeks on buy-in and education.

So why is the Team only 80% self-contained and not 100%? Because it’s expensive to eliminate all dependency. For example, payment systems tend to be costly to build. The Primary School Team is better off using the system built by a central Payments Team.

But the point here is that dependency is the exception rather than the rule.

Missions should be clear and about serving a customer

“Mission” is a key word in the 80% Rule. We define it as being about serving customers. There are two kinds:

- Real customers: the people who pay the company’s bills. Success is revenue, market share, customer satisfaction, etc.

- Internal customers: other teams within the company. Success is internal customer satisfaction (or even internal “revenue” earned by the team)

For example:

- The Primary School Team: serves real customers and is primarily measured by revenue

- The Payments Teams: serves internal customers and is primarily measured by internal customer satisfaction

Why not measure the Payments Team in terms of processing speed, chargeback rates or uptime?

While these metrics are important for the team to manage aspects of what they do, they are too narrow for the primary measure and can drive the team to do the wrong thing.

Teams should not have conflicting missions

Conflicting missions is a special kind of hell. For example, let’s say that the Primary School Team is targeting a customer segment that loves using XYZ payment card. XYZ charges a high commission and is slow to process.

Now pretend that the Payments Team has a poorly defined mission: process payment transactions quickly and cheaply. What happens? Many meetings. Resistance and heel-dragging. Uncertainty and blockage of Primary School’s initiative. And eventually an escalation involving a couple C-level execs.

The net result is expensive man-hours get burned, the Primary School team is a few steps behind competitors and everyone involved has a bad taste in their mouth.

Now pretend that the Payments Team had a well defined mission: provide payment services to the different education teams with satisfaction as their main measure. What happens here? A few meetings to ensure understanding and agree budget. And then everyone does real work.

Even if the Payments Team has reservations about what the Primary School Team is deciding, they don’t block them. With clear missions, decision-making rights (and responsibilities) are clear too.

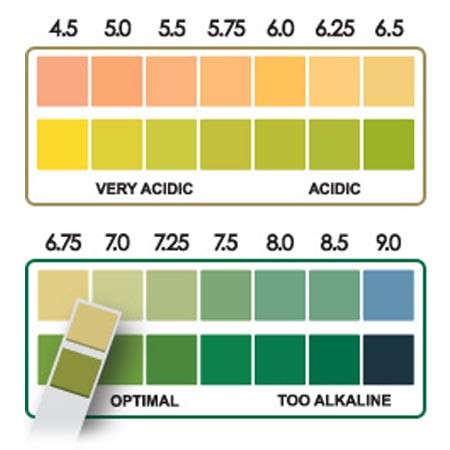

Litmus tests: have you set up your teams well?

Here are two questions to ask yourself about your teams.

1. Is the team in-question regularly bottlenecked by other teams? If so, it doesn’t have the necessary authority or resources.

2. When there is a disagreement between teams, is it clear which team is ultimately responsible for the decision? If they’re arm wrestling or escalating to senior managers, then their missions are probably unclear and conflicting.

If you find yourself on the wrong side of the test, don’t despair. It means there are some potential organizational wins in front of you.

GS Dun works with existing companies to launch and build new ventures. Our name is short for “get sh** done”, so while we can talk the talk, we prefer to keep our meetings short and just get on with it.